Chaitya Dhanvi Shah’s Ratan Parimoo, The Conductor

A Symphony of Expressions and Colours

Reviewed by Upender Ambardar

Book Reviews

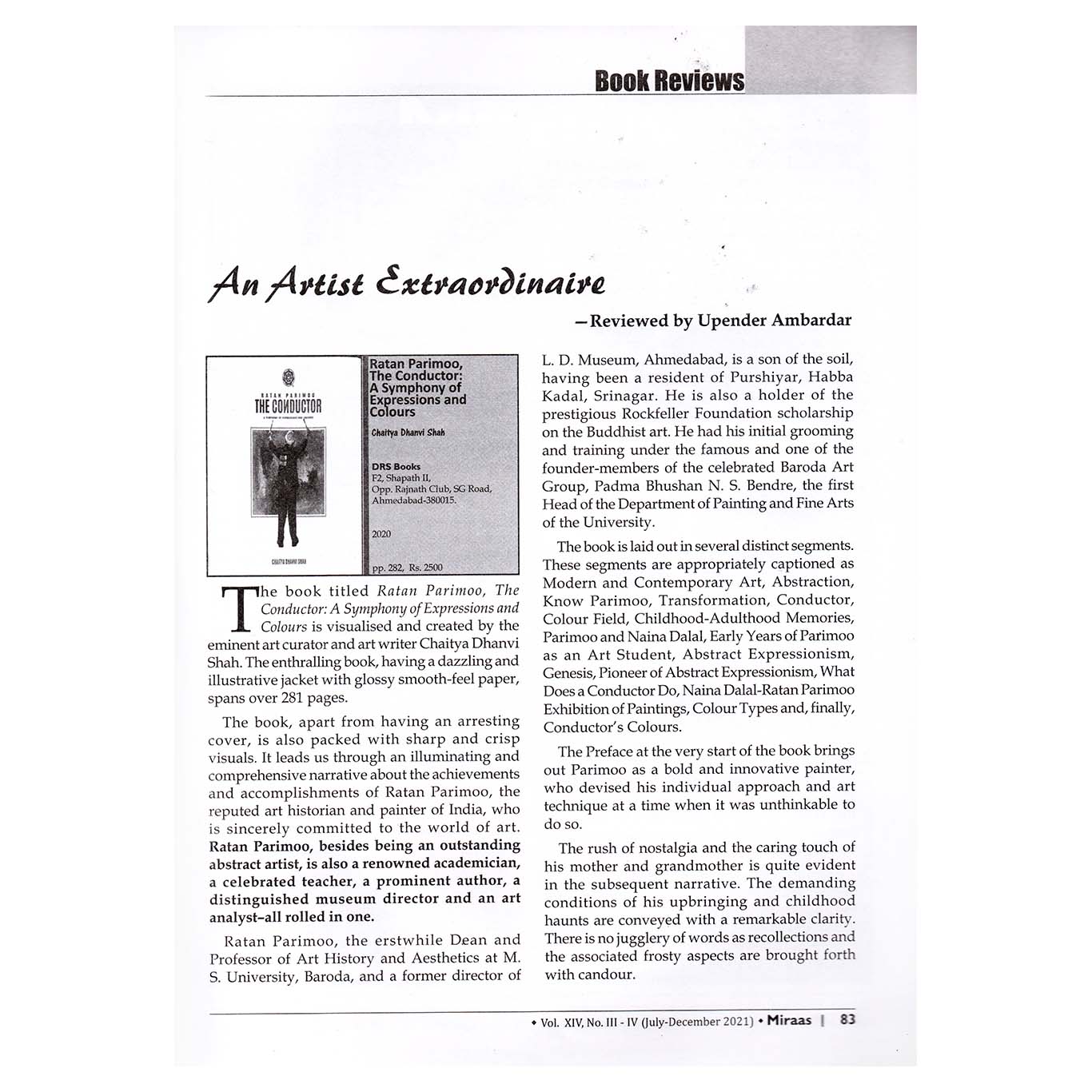

An Artist Extraordinaire – Reviwed by Upender Ambardar

Ratan Parimoo, The Conductor: A Symphony of Expressions and Colours

The book titled Ratan Parimoo, The Conductor: A Symphony of Expressions and

eminent art curator and art writer Chaitya Dhanvi Shah. The enthralling book, having a dazzling and illustrative jacket with glossy smooth-feel paper, spans over 281 pages.

The book, apart from having an arresting cover, is also packed with sharp and crisp visuals. It leads us through an illuminating and comprehensive narrative about the achievements and accomplishments of Ratan Parimoo, the reputed art historian and painter of India, who is sincerely committed to the world of art. Ratan Parimoo, besides being an outstanding abstract artist, is also a renowned academician, a celebrated teacher, a prominent author, a distinguished museum director and an art analyst-all rolled in one.

Ratan Parimoo, the erstwhile Dean and Professor of Art History and Aesthetics at M. S. University, Baroda, and a former director of

L. D. Museum, Ahmedabad, is a son of the soil, having been a resident of Purshiyar, Habba Kadal, Srinagar. He is also a holder of the prestigious Rockfeller Foundation scholarship on the Buddhist art. He had his initial grooming and training under the famous and one of the founder-members of the celebrated Baroda Art Group, Padma Bhushan N. S. Bendre, the first Head of the Department of Painting and Fine Arts of the University.

The book is laid out in several distinct segments. These segments are appropriately captioned as Modern and Contemporary Art, Abstraction, Know Parimoo, Transformation, Conductor, Colour Field, Childhood-Adulthood Memories, Parimoo and Naina Dalal, Early Years of Parimoo as an Art Student, Abstract Expressionism, Genesis, Pioneer of Abstract Expressionism, What Does a Conductor Do, Naina Dalal-Ratan Parimoo Exhibition of Paintings, Colour Types and, finally, Conductor’s Colours.

The Preface at the very start of the book brings out Parimoo as a bold and innovative painter, who devised his individual approach and art technique at a time when it was unthinkable to do so.

The rush of nostalgia and the caring touch of his mother and grandmother is quite evident in the subsequent narrative. The demanding conditions of his upbringing and childhood haunts are conveyed with a remarkable clarity. There is no jugglery of words as recollections and the associated frosty aspects are brought forth with candour.

The chronicle moving ahead tells the reader about his marriage with Naina Dalal, who happened to be his junior in painting at the university, in the year 1960. It was the time when he got selected for the prestigious Commonwealth Scholarship of the British Government to study in England for three years. Next, Parimoo familiarises us with his early days as an art student at the newly established School of Fine Arts, Baroda University under the inspiring guidance of Professor N.S. Bendre. It was here that the virtues of open-mindedness, individual creativity and independent thinking were imbibed by him. Under the caption ‘Parimoo and Art’, he makes it abundantly clear that he is wedded to the visual art as a lifetime preoccupation and in no way is an artist for the business. He also spills the beans about his involvement with the abstract and expressionist art styles.

Interestingly enough, he discloses that he continues to hold on to the elements of the Indian sensibilities and feelings through the use of styles and colours. He further says that he draws inspiration from his surroundings and landscape. He also makes it known that abstract art is analogous to music as both of them encapsulate a wide range of expressive and creative possibilities. Both of these, as per his opinion, are responsible for stimulating the corresponding emotional response. Parimoo also states that in abstract art, the accompanying visual elements are colours, lines, shapes and volume. Contrastingly, he opines, the obscure syllabary consists of movement, symmetry, rhythm and gravity. He also divulges that colours and brush strokes have a prominent place in this type of art. It motivates a painter to break away from the usual figure painting, portraits, landscapes and religious-cum-societal type of art. This forms a part of the narrative under the caption “Transformation’..

Revisiting 1950s with Ratan Parimoo comprises another segment of the book which is packed with the images of his early art work dating from 1956 to 1960. These were displayed in exhibitions at museums and art galleries of Ahmedabad, Mumbai and Vadodra. The upcoming pages

make us aware of the effects of reading books on art history and aesthetics which contribute to galvanising one’s creative outlook. Likewise, his familiarity with the literary writings made him comprehend the theory and subsequently helped in its transformation on the canvas in a practical form. Many of his earlier paintings are like a sojourn to his motherland Kashmir, for which he has immense emotional and fond recollections. It is amply demonstrated in his paintings of ‘Maej Kashmir’ series, in ‘Habba Kadal’, ‘Badam Wari’ and other paintings. They evoke the idyllic ambience and milieu of the 1940s and take the readers into a landscape that is identifiable to them. In the subsequent pages, the reader is also familiarised with the colour types, the associated connect with the society at large and their role in making the individual life and society lively, pleasing, high spirited and delightful.

The book rounds off with a bunch of impressive and vibrant images of his artwork. In sum, it is a landmark, an immensely readable work packed with extensive information about the art, life and achievements of Ratan Parimoo, the maestro of the abstract art.

Knowing Parimoo

Parimoo’s Childhood and Adulthood Memories

Parimoo’s childhood was a balanced shower of motherly love and struggles with his father.

Parimoo spent his earliest days at his maternal uncle’s (Mama’s) place sucking thumb, weeping hoarsely, kicking around his legs and arms, and wetting his underwear. He must have been a virtual terror for his mother.

As a child, Parimoo was weak and meek. His nose used to often bleed. Parimoo’s mother used to narrate stories of his childhood to him-of how he was born, what pain she had experienced while birthing him, how he had a tiny body and only his head was visible. It was a miracle for such a baby to be born normal and today being named among one of the celebrated artists and art historians of the world! The artist who left Kashmir at a raw age! The artist who was training under the redoubtable N. S. Bendre! The art student from the first batch of Baroda! The teacher under whom thousands of students passed out! The academician! The professor! And what not! Parimoo proved to be the master at every level of the art ecosystem.

Parimoo’s mother used to take extra care of him. Goat milk and mutton soup was Parimoo’s diet for a long period of time. Parimoo goes slow with this memory. The love for his mother can be seen in his eyes. Parimoo is very expressive when it comes to sharing his memories. His storytelling can get you in an enchanting zone. The setting of pre-Independence, the love of a mother, the beautiful Kashmir and a family story that most

of the Indians can relate to! Then what is so excitingly different about Parimoo’s story? The strength to go beyond the boundaries of his town. The guts to become a painter. The conviction to challenge the art arena in spite of having a difficult childhood. Parimoo proves that there is no need of better facilities and a better family atmosphere to excel in your field.

Parimoo’s reading hobby, curiosity to learn, discipline and understanding of art provided him the guts to cross boundaries, to dare and try something new, to tear down the routine of social norms.

Back home, he was a taboo for the family. He was not even allowed to sit on his father’s lap as he was always under the shadow of his mother. Parimoo’s elder brother was raised by his grandmother and was allowed to dance on his father’s lap and play with the cigarette tins as if they were dholaks. His father used to keep raw tobacco in those empty cigarette tins for his hukkah. The faces of Parimoo’s father and grandmother used to lit up with joy and glow like incandescent bulbs seeing Parimoo’s elder brother dance.

Gradually Parimoo learnt to speak. A bulbul bird would occasionally come and sit on the edge of an open window of Parimoo’s house. The bulbul fascinated Parimoo as it seemed to be a rare bird in comparison to sparrows, crows and mynahs. Often a fascinated Parimoo would rush towards the bulbul to catch it. But by the time he would reach the window, the bulbul would fly away. As an innocent child, Parimoo would cry, Buybuyo, vayo (‘Oh Bulbul, come back’).

Knowing Parimoo

The brothers would be writing on both the sides of the mashk and show it to their mother, wipe both the sides clean and write again till they completed writing 12 times. One fine day some homework was assigned by the tutor to Parimoo’s elder brother. The tutor would come every day with some books and read them aloud to Parimoo’s brother, who would then repeat the same after the tutor. The tutor would write something on the top line of the mashk, and then his brother would copy it down.

Observing all of this Parimoo too was excited to read, write and learn. Hence he also started sitting near the tutor. However, Parimoo remembers someone appear out of nowhere like a scary shadow and snatch Parimoo’s book, give him a couple of slaps and blows, drag him away from his brother and the tutor. On several occasions, Parimoo would steal books when all would be snoring in the afternoons, but it would end up with him getting caught. Parimoo’s family thought he was disturbing his elder brother’s studies. Beatings and curses were normal to be showered upon Parimoo in such cases. It is interesting to note how Parimoo, who started learning, reading and writing on his own will in his childhood, has become India’s most celebrated art historian today.

Parimoo picked up reading fluently and writing well. His calligraphy was out of the world. He had mastered the difficult art of peeling the fine point on the reed pen suitable for calligraphy. It is because of his sheer curiosity to explore, learn and gain knowledge that turned the person, who was beaten up for reading, into a person who went on to become a learned art historian and an artist. It is the same weak child who grew up to achieve several landmarks, including his Ph.D. publications and writings. It is his passion for reading that helped Parimoo in becoming a gutsy artist. His self-guided doctoral research on ‘The Paintings of the Three Tagores-Abanindranath, Gaganendranath and Rabindranath-made Parimoo receive his Doctoral degree in 1972. Parimoo’s Childhood Place

The place where Parimoo lived in Srinagar was known as Habba Kadal. There was a bridge across the river and the ghats near Parimoo’s

house, and a temple was visible from across, which appeared as if it was built over the water. Parimoo remembers the sun rising from behind the house, and young men swimming, diving and jumping from the side walk of the bridge into the river. The elderly imitated the younger men but did not dare to dive into the middle of the river. Parimoo remembers women washing clothes and utensils, while the men scrubbed and bathed little kids. The roads and lanes in Srinagar were of various shapes and sizes- smaller, longer, broader and narrower. While walking on those narrow lanes, Parimoo would suddenly hear the shrill sound of the whistle of a car, or hosh, bachao (‘save yourself’) of the tongawala harshly whipping his fearlessly galloping horse. There was no end to the roads lined up with shops on both the sides. There were houses of various combinations-tall, broad, short and narrow, tall and narrow, short and broad, tall and broad, short and narrow. Parimoo remembers crowds of people coming and going, cars, tongas, and men riding on bicycles.

Parimoo’s Memories with his Mother and Grandmother

Parimoo was very close to his mother. Even after seven decades, when I ask him how he remembers his mother, he is amused on how today, even at the age of 75, he still misses her. Being a father of two daughters and a grandchild, Parimoo still misses his mother badly. While recalling his childhood, the first person that comes to Parimoo’s mind is his Maej (the Kashmiri word for mother) and the second person whom he recollects is his grandmother (whom he used to call ‘Kakin’). It is impossible for Parimoo to remember his mother without being remembered of Kakin, with whom Maej remained entangled throughout her married life.

Reminiscing about the past, Parimoo becomes silent as he misses his mother. He feels nervous and guilty because his mother died long ago but he never stood up for his mother in spite of having grown up and having a good professional life. Parimoo feels that it may have never occurred to Maej that she was living a miserable life-she hardly complained, and never had any traces of melancholy on her beautiful face. She symbolised a typical Indian woman of the 20th century.

With teary eyes, Parimoo remembers his mother as ‘a beautiful lady, with a chiselled model look, fuller cheeks and tranquil expressions, buttoning up the shirt of my school uniform.’

Taking a trip down memory lane, Parimoo says that he was a smart learner and he picked up writing in Persian script at the young age of 5. He would write on a wooden painted plank with a reed pen (farsi kalam). Each time he completed writing on the mashk (both sides), he would show it to Maej and Kakin, and then wipe it off. He would repeat it and show it to both the mothers as witnesses that his homework was done.

Parimoo’s Grandmother

In Indian culture, the relationship that you share with your grandparents is the most beautiful memory one possesses of one’s childhood. Lucky are those who get this unconditional love and warmth from their grandparents. I believe it is more valuable than the relationship that you share with your parents. The amount of love your grandparents shower in the form of bedtime stories, gifts, taking care of food or life teachings cannot be compared to any educational model for a child in this world.

Grandparents can leave a deep impact on the character of a person. Parimoo was fortunate enough to have his grandmother, whom he

fondly referred to as ‘Kakin’ (grandmother in Kashmiri). His grandfather had died in his early years. Parimoo had high regards for the strength and bravery that he observed in Kakin as she singlehandedly raised his father and uncles in the pre-independence India. I feel that Parimoo’s ability to not worry about the world or the representation of his guts in his works might have come from none but his grandmother.

Parimoo’s grandmother was a simple yet strong lady. The entire neighbourhood would come and ask her for advice. His Kakin was a storehouse of traditional knowledge and wisdom. Being illiterate, a wall-clock or an alarm-clock or a wristwatch was of no use for her. But she would be sitting overlooking the window, with her thoughtful expression and chin resting on her right fist, and would observe the sunshine inside their compound and the adjacent house façade to gauge the time of the day.

Kakin would insist Parimoo to read out Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas to her. He would recite the verses (chaupai) imitating the intonation of elders that he had earlier overheard. His Kakin would sit and listen reverentially in spite of the fact that she did not understand a word. And even though Parimoo too as a child did not understand the meanings, he enjoyed the fact that Kakin appreciated him for performing the role of a bhakt. As he looks back, Parimoo feels that it was because of Kakin’s mental lucidity that his family was managed in a cohesive manner.

Kakin was destined to breathe her last in their ancestral house at Porshayar, thereby fulfilling the cherished wish of a typical Indian woman (to die in one’s husband’s home). She passed away in her bed one day, without causing any trouble to her family members.

Parimoo’s Memories with his Father

Parimoo recollects his father, Amarnath, wrapping himself up in a woolen blanket after the beds were made, while Parimoo and his siblings assembled around him. Amarnath would then narrate a story. Sometimes he would ask the kids to collect shirts which were torn and which had buttons missing. Parimoo’s shirts were always torn or had buttons missing when he returned from school or play. Amarnath would teach the kids how to stitch buttons and fix holes in socks. In the later years, when Parimoo was able to read, Amarnath used to get books and encyclopedias of general knowledge and read those books along with the children. Parimoo’s painting series exhibited at Marvel Art Gallery in 2010 titled ‘Revisiting 1950s with Ratan Parimoo’ has some fine examples of his narrative style of paintings. Those paintings seem to be inspired from the bedtime stories that Parimoo listened from his father-the visualisation in the paintings can be traced to the use of minute characterisation, detailed observations and capturing of the entire ambience.

Parimoo’s father always smoked before sleeping. Parimoo would lay beside him curiously, watching his father smoke. Amarnath inhaled deep and puffed out a lot of smoke. As a kid, Parimoo liked watching this hide and seek of the red tip of the burning cigarettes. During that phase, Parimoo felt protected being with his father.

Often his father would don a tightly wrapped white turban and put on ‘nice clothes’, which were completely different from what Amarnath would wear while at dinner or during the time of bedtime stories. He looked elegant in those clothes.

A lot of times Parimoo went up the hills for picnic and the journey used to be very picturesque with trees lined up on both sides of the sinuous river that looked like a gigantic serpent to Parimoo. Picnics like these were a great chance of bonding for Parimoo with his father. On a subconscious level, the picnics also expanded Parimoo’s vision to appreciate nature and its beauty. The colours, forms, shapes and, most importantly, the thought process might have helped Parimoo a lot during his painting phase.

In the summer vacation of 1966, Parimoo was informed of his father’s ill health. He was surprised to see his father become a schizophrenic, sitting for long hours near the window of their ground floor and continuously coughing. Parimoo used to be a sympathetic observer, sitting with his father and hearing him mumble nothings.

Parimoo recalls how his father never made any efforts to help his mother grow intellectually-that could have helped his parents communicate better with each other. These thoughts motivated Parimoo to take the initiative of choosing an artist as his life partner, so that they could share common interests and have common goals. Parimoo later discovered that his father had been jealous of him for having chosen a girl of his liking and having got married to her.

Parimoo’s father had joined the army as a recruitment doctor during the years of World War II (1939-1945) and was posted in Jammu. His memory of the World War is in the context of German invasion, battles in France, bombardment in London, followed by both German and Japanese forces losing, and ultimately the dropping of atom bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, which brought an end to the War.

At that point of time Parimoo was studying in fifth standard at the Missionary Primary School and had been chosen by his teachers to write the latest news on the black-board every day in Urdu language. Thus, in 1945, at the age of nine, he got acquainted with this tragic episode of 20th century history. This incident brought Parimoo closer to understanding the world history, the global news and provided him an exposure to the world affairs.

Parimoo and Naina Dalal

Parimoo fell in love and got married to a Barodian girl Naina Dalal in the summer of 1960. Naina was a student of painting too and was two years junior to Parimoo. When Parimoo went to Kashmir in the summer vacation of 1959, he had already spoken to his grandmother that he had chosen a Gujarati girl as his life partner. It was an incredible surprise for Parimoo when his grandmother immediately gave her consent and jokingly commented that she had already expected that he would choose a non-Kashmiri girl.

The year of his marriage was fortunate for Parimoo in many ways. He got selected for the Commonwealth scholarship scheme of the British government to study in England. The scholarship enabled him to study in London for three years. Naina took up a photography course and joined Parimoo in London. It was an exciting exposure for the couple into the art world at global level. Also, the Faculty of Fine Arts in MSU appointed Parimoo as a lecturer for ‘Art History and Aesthetic Objects’ on a permanent basis.

Parimoo and Naina returned from London in July 1963. Meanwhile, Parimoo’s father requested him to move their family from Kashmir to Baroda. Naina was seven months pregnant when they returned to Baroda, and for practical reasons (Naina’s brother was a doctor) she decided to stay at her mother’s place throughout the rest of her pregnancy. Naina delivered a girl in September and they lovingly named her Gowri.

Those were the days when a lot of things occupied his mind-looking after parents, grandmother, wife and the newborn baby, new home, and new teaching responsibilities. Having so many things running through his mind might have resulted in an outburst of his feelings, expressions and emotions on the canvas-through colours, through shapes, through strokes. His restless mind wanted an outburst, but he could not do so owing to his family responsibilities and his nobleness that did not allow him to be disrespectful towards his elders. But all the discomfiture and apprehensiveness found its way in abstract expressionism in his paintings.

Parimoo’s exposure to reading, being exposed to various painting techniques, his understanding of art combined with his intention to effuse his sentiments and traffic of thoughts found a constructive way of bursting into a blank canvas with colours and strokes. But all the discomposure and apprehensiveness found its way in abstract expressionism in his paintings.

Early Years of Parimoo as an Art Student

Recalling his experiences at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Parimoo exclaims that he was fortunate to be amongst the first few batches of Baroda’s newly established School of Fine Arts and having got the opportunity of directly working under Principal and Guru N. S. Bendre (1910-1992), along with Jyoti Bhatt and Shanti Dave.

The key role in Parimoo’s growth as an artist was that of Bendre, who taught between 1950 and 1966. Bendre owned a wide range of proficiencies as an artist and was widely appreciated for the importance he gave to classroom time by engaging students with planned activities, what he called as ‘studio hours.’

Parimoo was a voracious reader of English literature and had no difficulty with English language because of his missionary school background in Srinagar. He was one of the earliest students to complete Master’s Degree in ‘Creative Painting (1955-57) and write Master’s Degree thesis on his project ‘The Use of Calligraphic Line in Painting’. This laid the foundation of his upcoming series of paintings as a recipient of the cultural scholarship.

His Master’s degree thesis was built upon the theory classes of Markand Bhatt and V. R. Amberkar along with his own understanding of Rudolf Arnheim’s writings. Markand Bhatt’s classes constituted of ‘Fundamentals of Art’ in 1st and 2nd year, followed by ‘Plastic Values of Indian Art’ and ‘Plastic Values of Western Art’ in 3rd and 4th year respectively. In these classes, the students were not only introduced to Indian and Western art history but also got familarised with the concepts of ‘form’, ‘structure’ and ‘style’, and how these components have to be individually mastered and manipulated such as line, colour, space and volume. In the post-graduate classes, Amberkar furnished breadth and depth to art history and aesthetics-related subjects.

Parimoo’s brush-work is too broad and bold for expressionism. Just like Professor N. S. Bendre, he too achieved a convincing marriage of the figurative and the expressionist. He was also a fine colourist.

Parimoo sensed that the Fine Arts faculty at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, unlike other fine arts colleges, was free from any kind of conservative and provincial arts school atmosphere. From the point of view of the university authorities, the objective of establishing the first bachelor’s and master’s degree in fine arts and performing arts was to strengthen these arts in the Gujarat region. The new art educational philosophy began with what can be called a clean slate-to avoid the mistakes of older art schools. The teaching of naturalistic techniques should not be considered an end in itself. Likewise, the exercises based on traditional elements of Indian art, both in miniature paintings and in figural sculptures in stone and bronze, should not be looked as something sacred.

Keeping up with the socio-political spirit of the times, Parimoo and his co-students imbibed virtues of moving towards freedom, open- mindedness, creativity and individuality. By the time Parimoo reached 4th year, he vouchsafed individual creativity and thinking that were projected as almost unwritten slogans in the faculty campus by many revolutionary artists of the 19th and the 20th century Europe. For the first time, there was an institution that did not worry about trivial art lessons but made ‘contemporary art in the making’ as the vision for young students.

This series reflects the mind of Parimoo being influenced by the foundation laid by N. S. Bendre, the philosophy of M. S. University and the institutional approach of the management and faculty of MSU.

Besides the persona, demonstration and the colour exercises, Bendre’s teaching strategy included compositional exercises, especially of shapes, textures and colour tones. One of the exercises included cutting a photograph in four sections. Each of the pieces was further cut up and was passed on to different students. Whatever set of black and white shapes that one received, one had to rearrange them in equivalent colours and tones. Through such exercises one was able to relate to the works of Matisse (for colour) and to Cubists for collage and abstraction.

Bendre’s significant advice would be ‘now that you know the compositional elements and the colour values, ask yourself what you wish to do and find your own way.’

By 1958, Bendre had moved towards ‘pure abstraction’ and his handling of drip paint as well as how to finish a figureless painting added to a further repertoire of his demonstrations. These experiments can be considered as one of the reasons for Parimoo’s inclination towards abstraction.

The First Baroda Group of artists (formed in 1956) has a great emotional significance in Parimoo’s career as a young painter. It was

Bendre who suggested to them to form a group of artists with the objective of working together and exhibiting together. Several consecutive exhibitions under the banner of Baroda Group were held (and well received) in Bombay between 1956 and 1961. The exhibitions reflected the historical spirit of those times, which was already unfolding through the formation of modernistic groups viz. Calcutta Group (1943), Shilpi Chakra of Delhi (1946) and Progressive Artists Group of Bombay (1947). It was during these years that Bendre discussed some of the complex dilemmas of the Indian artists. These ideas reflect a ‘philosophical’ significance in comparison with the practical demonstration given in the studio.

The important or the significant reason of mentioning details about the First Group of Baroda is purely because of historical necessity. Parimoo, having been uprooted from a far corner of the country with least awareness of what it is to be an Indian and having been transplanted into a region which inspired the consciousness of being a characteristic Indian-for him, belonging to the First Group of Baroda Artists was like being anointed into the emerging contemporary art phenomenon of the country. The first exhibition was held modestly on 21st April 1956 at a small gallery at the Centre at Rampart Row. A pocket- sized book listed the following names as the first artists of the exhibition-Santosh, Ratan Parimoo, KG Subramanyan, Prabha Dongre, Kumud Patel, Shanti Dave, Trilok Kaul, Vinay Trivedi, N. S. Bendre, Balkrishna, Jyoti Bhatt, Praful Dave and Ramesh Pandya.

Parimoo and Art

While researching and interviewing Parimoo, I was amazed to see the contrasts of him as an artist as he paints abstraction and how noble, polite and soft-spoken he is as a person. When I ask Parimoo to describe himself as an artist, he says, ‘I am not an artist for business. I am wedded to the visual arts as a lifetime preoccupation.’

‘I am not an art historian who also indulges in paintings like Dieric Bouts, a critic had quoted Parimoo while commenting on his solo show of paintings and drawings in 1976. Parimoo had added: ‘My choice of art history was deliberate in the way a painter would feel like diversifying into printmaking or sculpture making.’ Studying various cultures have always fascinated him. During his student days (1950s) he would look again and again at reproductions of Japanese prints, Tibetan cars and tankas, African sculptures, Indian miniatures, and European paintings and sculptures. Going abroad at an early age to study in London University (1960) provided him with the opportunity to see thousands of paintings and sculptures in real, since he could easily travel from one European country to another.

Studying visual arts as a common heritage of mankind gives a better insight into the fundamental questions of creativity and creative expressions in the human society. It is true it has been difficult to relate a creative artist and an art historian.

Due to extreme poverty in our country, our social and political priorities are removal of social inequalities. And making works of art, encouraging the artist community, creating opportunities for artists, and to participate in expressing or responding to art-these are the last priorities in the minds of our leaders; and even our society as a whole shows least interest in the endeavour.

Growing up in a middle class family in Kashmir was not sufficient enough for Parimoo to get acquainted with the culture, beauty and complexities of Indian life. Having seen beautiful lakes and mountains and pleasant climatic conditions in Kashmir, Parimoo could not reconcile with the dazzling sunshine, sandy riverbeds and empty fields in Baroda. That made Parimoo feel nostalgic for Kashmir and he painted

Kashmir in that phase.

Knowing Parimoo

Parimoo’s paintings can be grouped in three phases:

(i) His ideas changed due to his widening experience as an art history teacher.

(ii) The numerous works he had seen of various artists and the qualities that he learnt to admire, leading to a deeper understanding of creativity.

(iii) His own experiences of life in his country and his grasp of Indian tradition and contemporary art district output in India through several decades.

His creativity as an Indian artist is hemmed between contemporary aesthetic ideas and the rich Indian artistic heritage of the past. Parimoo’s first phase (late 1950s) was the outcome of his training which made him analyse the perspective and line, when his paintings depicted his visual experiences of things seen by him or remembered by him. Then came the second phase (1960s) where he found himself circumscribed by method, wherein he strived to get rid of lines and began working simply with colour and gesture surfaces. Post-1970 (the third phase) Parimoo made a fresh beginning and found himself developing into an introvert and brooding over his own world of fantasy. This kindled his interest in mythological imageries and situations, and his paintings of this phase portrayed his fantasies and fear.

(Gratefully taken from Chaitya Dhanvi Shah’s Ratan Parimoo, The Conductor: A Symphony of Expressions and Colours, DRS Books, Ahmedabad, 2020, pp. 61-93)